Before the November 1 elections, you said that the elections results could in fact not be predicted and that the situation at the time was full of uncertainties. In a sense, you turned out to be right. What was it that led you to make this comment about the elections, to use adjectives like “weird” or “surreal” with respect to the recent social life in Turkey?

For the last five years, we have followed a monthly moral index, which is similar to a consumer confidence index. Especially in September and November, the expectation of a crisis among the population has reached the highest level in this five-year period, 75%. In other words, three out of four people in the country said that “I’m expecting a big economic crisis in the next three to four months.” A government could not be formed, negotiations were held to form a coalition, etc., so we asked the question, “How do you evaluate these five months?” 82% of people replied that “this is a big political crisis.” This is the second data. Third, we asked the question, “How do you consider the current environment of battles and terrorism?” and the percentage of those who regarded this problem as an immediate problem capable of directly affecting their everyday lives rose to 62-63%. Emotionally speaking, all these three data pointed to an extremely worried, anxious society whose expectations completely transformed into despair and pessimism. On the other hand, you look at political choices and they seemed to be the same as they were six months or one year ago. If we suppose that the percentage of those saying that they would participate in the elections rose to 50%, this would be an indication that could lead us to say that they are showing a reaction to politics. All these political findings showed us, as it were, nothing changes, but when you look at non-political findings, everyone sounds the alarm. This was what I called weird. If the determining factor in the motivation for election is fear, anxiety or worry, we cannot measure behavior driven by fear, anxiety or panic either in a laboratory environment or with a survey. What people can do in a moment of panic is not something measurable. Four out of five people in the country believed that recent developments amount to a big crisis. And one out of four people believed that there would be a crisis in the following three to four months. This state of mind did not seem to me to be a measurable thing.

So what was it that led to the picture resulting with the November 1 elections?

This picture was drawn neither by hopes and utopias nor by promises and lists of candidates. It might be the case that, among fifty-four million voters, 100,000 people voted just because Beşir Atalay was again a candidate or there may be 120,000 pensioners saying that they had been promised a 100 lira increase in their salaries, but the determining factor for the votes and main characteristics of 47,000,000 voters out of 54,000,000 voters was not hope but fear, anxiety and search for the peace and harmony for the household. This was not quite measurable. The weird fact or the surreal situation was that no picture was reflected in the political data. According to political science, if there is a power ruling the country for thirteen years, people would naturally turn toward the power, not to the opposition, in such times of crisis. The fact that the power did not receive its share from this crisis, but, on the contrary, gained an increase in its votes is not something quite predictable or normally acceptable; this is something quite surreal. Looking from 2002 to November 2015, the AKP showed a normal rise until 2011, then a decline. Such a tendency to rise and decline is valid for every product, idea, party or brand. Nonetheless, this was not a real decline, as they managed to bounce back without any void in power, which is something rarely experienced in the world. And this was led by the fears, anxieties, and perceptions of threat regarding the peace and harmony for the household.

The AKP lost a great deal of its votes in the June 7 elections, yet its 40%, was still quite high in consideration of the recent political history of Turkey. Was this 40% of voters, which supported the AKP against all odds, an attractive core for the November 1 elections?

With 54 million people, every party has a core vote. Some people have intellectual or ideological leanings and some people have emotional leanings. Just as I cannot explain why I am a Galatasaray fan, some people have a liking for a leader. Every party takes its core vote from these 54 million people. As for some of the rest, we call them sympathetic voters. It might be the case that they completely set their heart on that party, or that their ideological leanings do not coincide with that of that party, but they vote for them for some reason. Being among the core voter within the party, s/he then shifts to being a sympathetic voter when she begins to criticize it. If her criticisms continue, she shifts into the grey area. In that grey area, she then becomes a neutral voter, beginning to listen to another party and paying heed to what they say. If she has not still heard something stealing her heart or reason away, she goes back to what is familiar during the election. One of the determining factors in this picture is the absence of political competition. The CHP (Republican People’s Party), the MHP (Nationalist Action Party) or the HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party)—the HDP being of course much different than the other two—were not able to generate a utopia that would attract great masses or those social segments would have turned away from the AKP. People naturally turned to the AKP. The total number of the AKP’s core voters is 18 million. Compared with the total number of 54 million voters in general, this adds up to 35%! Depending on the voter turnout, this 35% amounts to 42-45%. With the help of its sympathetic voters, the AKP’s share of the vote has thus far shifted between 41% and 47%. On June 1, this was 18.5 million people; their core voters were locked in. From December 17 onwards, the AKP gradually lost approximately 2 million of its voters to the MHP. And they lost approximately 1.5 to 2 million voters to the HDP, but that core was not eroded and remained very steady. Since the core of other parties could not produce something sufficiently strong, a considerable portion of sway voters again turned to the AKP. Along with fear and the absence of political competition, there is an ongoing polarization between those supporting the AKP and those opposing it. Against three other parties, the AKP came to power alone and we knew even before the election how 38 million people would vote, no matter the circumstances. There is a core of 18 million AKP voters and and 20 million votes are distributed among three other parties. Between 54 million general voters and 38 million core voters there is a grey area with 16 million voters, a segment not yet committed to the mental and emotional embargo of this polarization. Whatever Recep Tayyip Erdoğan says, 38 million voters are categorically either for it or against it, but the people within the grey area can, for example, say that “the AKP can be right in three events and wrong in five events,” which indicates that they are a sensible social segment. The result of the elections are determined by the turnout of non-polarized 16 million of people within the grey area and their specific political behavior in the election. The grey area shifted this time to the AKP.

These people cannot be monolithically defined as the educated or the uneducated, or working or unemployed women. These are people who, unlike the other 38 million people, have not elevated politics to be a subject or main center of their lives. For one thing, among 54 million voters, there are 6 million people who are not interested in the elections anyway, as they only read the sports pages of newspapers. Approximately 35% of voters, i.e., about 20 million people, vote in intellectual accordance with their parties; we call them ideological voters. They may not literally know the party program, but if they call themselves conservative Islamists, what they naturally think of is the AKP. Approximately 25% of voters, i.e., about 14 million people, relate not to the party but to the leader. Tayyip Erdoğan has this charisma. And there is an approximately 20% of voters, i.e., about 11 million people, whom we call emotional or supporter voters. Finally, there is a group of 10% of voters in which we are also included. They think they know everything and complain that “none of these parties is mine,” but vote for one of them in the end anyway. Another 10% is the total opposite of us.

In this case, we are talking not about a society estranged from politics over the years, but about a highly politicized one.

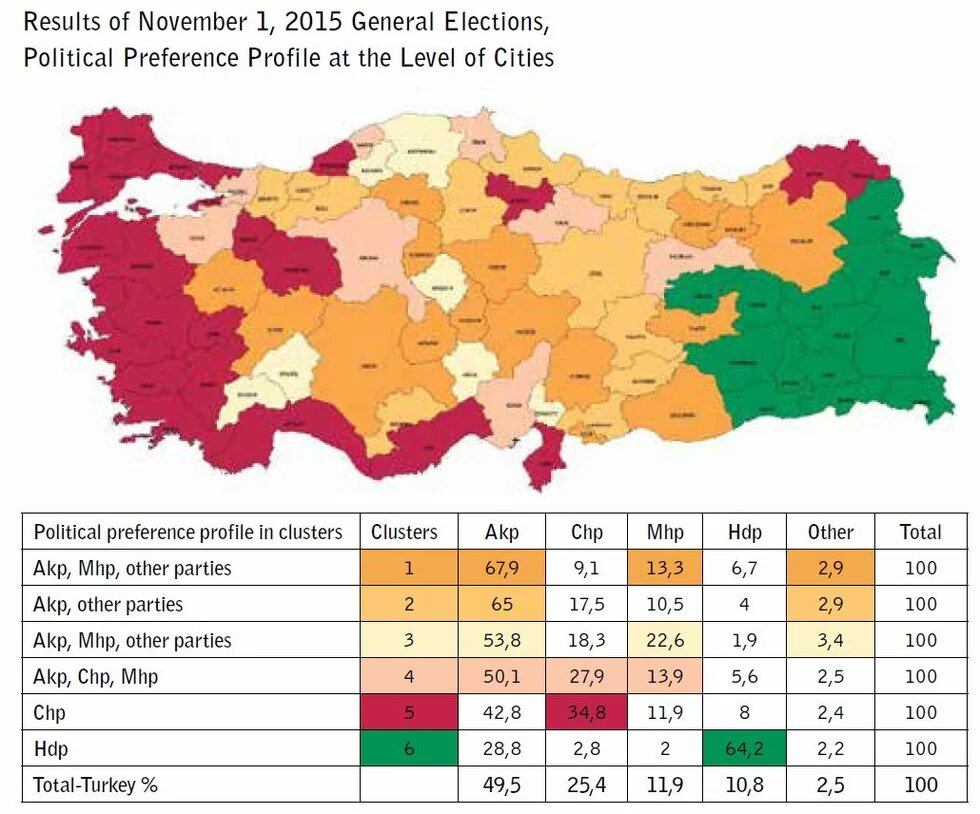

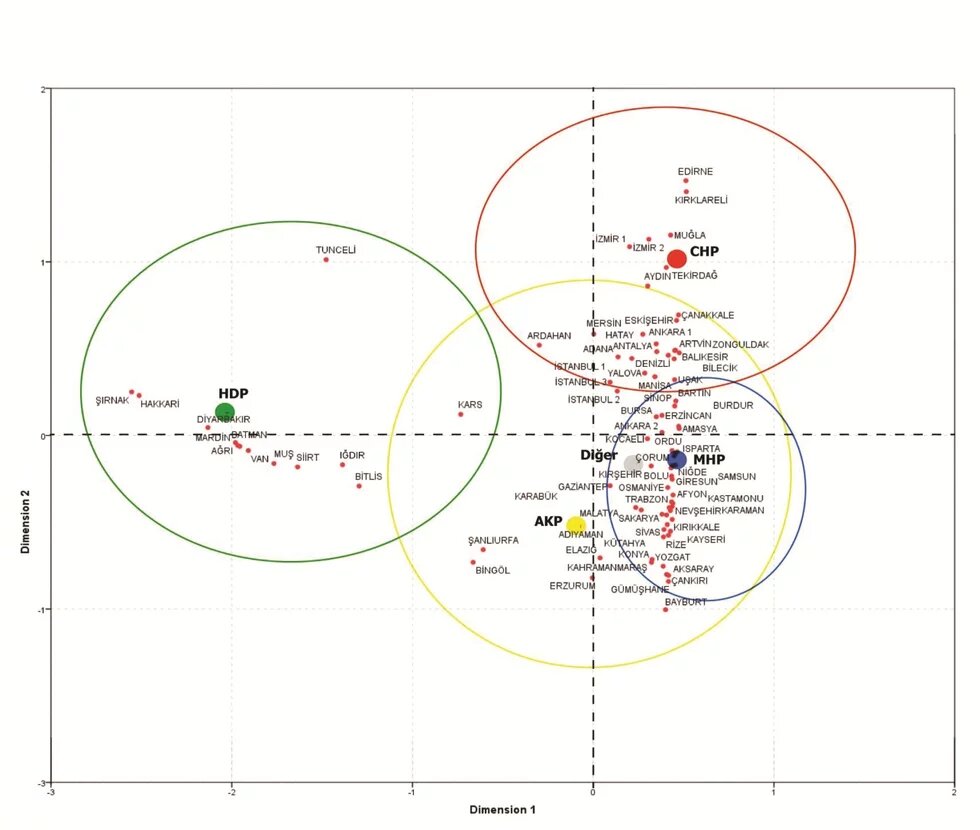

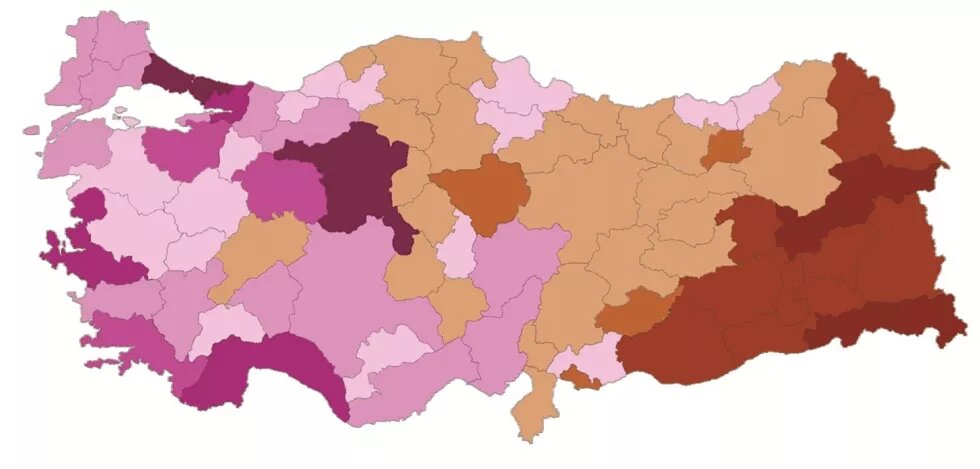

To be more precise, people have strong frames of mind. The most important determining factor in this election was the following: politics in Turkey was locked up into identities. And this is such a time when commonsense does not work at all. Two figures in our November 1 Ballot Box Analysis report offer a very clear understanding of this issue. You instruct the computer to distribute over the outer space, like a constellation of stars, the similarity, closeness or distance between the 81 provinces in terms of election results. And then you begin to make sense of this, trying to understand on what basis it has distinguished them. One of the significant distinguishing axes in politics in Turkey is the discrepancy between Turkish and Kurdish provinces. It is relatively easy to explain this discrepancy, but how can one explain Edirne, Kırklareli, İzmir or Aydın? There are a series of explanations for this. For example, one can distinguish them on the basis of their socio-economic level of development, and this is not only an economic level of development. There are also many data, such as seats in movie theatres, number of books sold, hospitals, and the number of beds per one hundred people. TÜİK (Turkish Statistical Institute) calculates all these figures and publishes annual reports, comparing 81 provinces in terms of these data. It is also possible to term some developed provinces, and others undeveloped. The provinces under the influence of the HDP are the most underdeveloped provinces, those under the influence of the CHP are the most developed ones, and those under the influence of the AKP are places with a desire to develop. One can also define these provinces in terms of education, as undereducated or highly educated provinces. And there is another third axis, with highly religious provinces, on the one hand, and provinces with tenuous religiosity, on the other. It is possible to define the four corners of Turkey as Kurdism, Turkism, religious and secular. This is where politics in Turkey gets stuck. This mapping shows the spatial successes and failures of the bicentennial story of development in these lands. It is also possible to say that these four identities, these four parties are products of a historical process. The current polarization seems to explain the issue, but if you look a little closer, you can see the determining historical processes at the bottom.

The HDP always tried to overcome this to the best of its ability and took 13% of the votes in the June 7 elections, but Kurdish nationalists and PKK stood in their way. This is now just a dream. If it had really been successful, it would have replaced the CHP and risen to 25% with the secular voters. From 1983 to 2002, the party winning the first place in general elections has always been a different one. In one period, it was the SHP (Social Democratic Populist Party) that came to the fore, then it was the DSP (Democratic Left Party), then the Refah (Welfare) Party and the MHP… Since 1987, a time when sociological, social, and demographic change in Turkey was at its fastest momentum, there has been no future vision agreed upon by society as the whole. Therefore, the winning party in the general elections always varied, which means that society gave each of them a chance. Whether the DSP, the SHP or Refah came to power just because it was their turn or not is a separate matter of debate, but they must have done something different as the electorate predominantly voted for them. Therefore, the AKP is a product, a result of a process. Moreover, it is a product of a period full of great social changes: the level of education, computers, transportation, roads, cars, planes, mobile phones, exports, globalization, the information society… At a time when whole life changed due to both global and internal dynamics, society searched for an answer, a vision, but could not find it in any party. On the other hand, there was a time when the whole system hit the wall in dismay: the February 28 coup, the 1999 Marmara Earthquake, and the 2000-2001 economic crisis. Within these four years, all social systems came up against a brick wall. AKP used the time between 2000 and 2007 in a proper way. If it had continued its path in the former Welfare Party, it would not have been able to grasp this opportunity. Perhaps, first coming to power alone, the AKP would also have used its turn and it would have been another party’s turn in 2007. But it made use of this opportunity and the whole story turned to a different channel.

The AKP has formed one of the strongest governments in the history of the Turkish Republic, but how can we explain the fact that they maintain this strength after thirteen years?

Together with November 1, we have had 18 general elections and five very critical ruptures in our history. The first was the 1950 elections, the Democrat Party against the party that founded the republic. In the 1961-65 elections, it was the Justice Party against the coup and generals; they hanged the leader of the Democrat Party on the grounds that he had sold the country, but the same party came to power alone five years later. 1973 was Ecevit’s success. In 1983 it was Özal, despite generals. And finally the AKP. You know what some people say, “doesn’t the society in Turkey want change and democracy?” What better indication than all of these things? All ruptures are in favor of the party purporting to change the whole system. And if today there were another party, purporting to really change the system, giving confidence with its cadres and words, a party outside the current ones, it would secure the votes.

The AKP has two faces that totally oppose each other like night and day. On the one hand, it is a reformist party, that claims to change a number of things; and on the other hand, there is a party that has not done anything for this cause in the last four years. It is a strange that even Tayyip Erdoğan says today that “the system has got stuck, thus we have to renew the system.” He also says “let’s change the constitution” to which the CHP replies “we shall not negotiate the first four articles of the constitution.” The one in power says “the system has got stuck,” and the one in opposition says “we should not change the system.” The AKP’s government program with declaring elections and a transparency package is more comprehensive than the CHP’s. Whether or not they will be successful, or whether they are sincere in these demands or not, those are separate matters of debate. But in terms of perception and image, it is still the AKP presenting itself to society as the one saying “we should change the system.” And society is extremely anxious, aware of the problem in Syria, the battle situation, the shot down Russian jet fighter… Yet we do not know the extent of society’s consent or to what it will give its consent. Looking on the basis of current actors, here is how I see the situation: Looking at the situation whether with the eyes of Kurds, women, Alevis, environmentalists, or whatever, it is a fact that one hundred or two hundred years of development or modernization model has been blocked in Turkey. We have nowhere to go. All of our problems are in front of us for all the world to see; all of them are simultaneously not only visible but also at a configuration where they lead to violence. Even environmental protests are carried out with violence. Therefore, the problem is the problem of renewing Turkey’s model, and all actors feel the need to do this. Also within the AKP, there are some people wishing for the maintenance of the old system or some who desire to establish or search for a new model. The CHP and the army also feel it. The country’s salvation depends on the question where the reformist, progressive wings will predominate. This was what excited me about the HDP, the part to which I tried to make a contribution. There is another issue capable of affecting the whole play: How long will Tayyip Erdoğan continue his blind insistence on the presidency, or how long will he continue his controlled crises in order to force society to agree upon presidency? Of course, there is also a third element: The Middle East. Two states previously known by the names of Syria and Iraq are now gone, but more fatefully, the points where the 200-year old model has gotten stuck are also the problems of the region. Sectarian or religious wars in the region will also become our internal problem tomorrow. The Kurdish problem has always been an internal problem anyway. Citizens gave their votes, and yes, they gave a support not expected even by AKP itself, and now they have taken a back seat, waiting to see whether the party they voted for will figure out a solution or not. But if these solutions are not found, I am not sure whether society would give its consent to continually live in the midst of this uncertainty coupled only with identities and polarization.

Is the mass of people within the grey area one that can be easily manipulated by the AKP, a mass that can easily be persuaded into either peace or conflicts?

I think that the AKP was really successful until 2007. Following Ergenekon, Republican rallies, the April 27 E- Memorandum and a host of other problems, the AKP realized that there was no constellation within the bureaucracy and the state with which it could form any alliance, and it thus formed its line of defense in the street. Some part of this line of defense was carried out as a practice of the social state, perhaps as policies of conscience, but it immediately moved on to use this relation and the growth in economy as a means to transform masses into supporters of the AKP. From 2010 onwards, steps were taken toward the third phase; following the 2010 referendum, gaining of 58% of the votes and the dramatic Gezi events, this turned out be a transformation of AKP supporters into supporters of Erdoğan himself. He fabricated this process even while arranging lists of candidates and election declarations in 2011. The lists of candidates in 2011 are the AKP lists with the highest number of statist bureaucrats. It was then that Muammer Güler and the like showed up on the lists. Showing its determination not to shy away from its rule limiting members from running more than three periods, the AKP also liquidated dissidents within the party. And Gezi led to the transformation of the masses, who just became supporters of the AKP and into supporters of Erdoğan. Those 18 million votes were secured not all of a sudden, but step by step. What about now? How will the AKP be able to maintain 4-5, 5 million people, whose votes it gained with the overall 23.5 million votes in November 1, following the 18.5 million votes on June 7? It seems that they are now going on with strategy of national pride, fighting with the hegemonic powers of the world. Does this strategy work? Yes, it works. It works because chauvinism is strong in these lands. There is of course an inclination toward authoritarianism. Belief in the rule of law is already low. There is a predominant search for a leader by those wishing not for legal mechanisms but for a strong man deciding everything, so there is a social state of mind that might lend itself to its realization. On the other hand, this is not the old Turkey. 93% of the people live in cities and 52% of this 93% live in 11 metropolises. The distinction between a city and a metropolis is as the following: Uşak is a city, so too is İstanbul, but the relations of solidarity, moral and cultural codes in Uşak are not the same as those in İstanbul. The social groups behind the AKP, whom we call modern conservatives, have also seen another world; they think in global terms and take part in global business. Behind Mr. Erdoğan, there is a social group comprising 23 million people that would unhesitatingly give a leg up for dictatorship. But there is also an opposite climate.

As Konda, we gave up following this process in 2014 and after all, this social support was never at 80-90%. Even if it had been so, they would have been asked why the solution of this problem was being delayed if there was 90% support for it. But this is not the case. The Kurdish problem is primarily a problem between Kurds and the state, but in the 40-year period when this problem continued without being resolved, it gained a second social aspect. When the peace process started in 2013, the support level was 35-40% and the percentage of those opposing it was about 30%. The masses in between were unsure, yet the support level has always been high among Kurds. From January to July, it rose to around 55% and the percentage of those opposing it decreased. However, it then began to decline from 55%. And by the end of the year, it had returned to its previous situation. We penned an evaluation report where we said that we will not measure this anymore. For one thing, the promises of this process to society in general were not certain. Let’s say that we have made a peace, but what do we mean by this and what is going to happen tomorrow? The government’s shortcoming was that they did not explain the will to co-existence, democracy, and cultural pluralism. There was a limit to commonplaces or lofty phrasings like fraternity. But there was a need for different interactions between civil society and local administrations, a need for the proliferation of sites and actors. Most importantly, other formal negotiations had to be carried out in the parliament in the legitimate political sphere. Besides, the problem of trust between the two parties could not be overcome. No effort has been made to resolve the paranoia among Turks about the division of the state and the suspicion among Kurds about a possible deception. But as of today, everyone wants to restart with the Dolmabahçe consensus, which was not sufficiently backed when it was first declared. And this is the paradox. If it had then been backed with heart and soul, the thing called the Dolmabahçe consensus would not have been so easily sacrificed.

Is this their highest vote, not in terms of the number of parliamentarians, but in terms of the overall population?

Except for the results of the June 7 elections, it is the first time the AKP secured such a low number of parliamentarians. On the other hand, in terms of its electoral base, it increased this figure to 23 million—the previous highest figure was 22 million.

Is this the picture that allows Erdoğan to say we should “adapt the constitution to the actual situation?”

What we experience is the return of model that is two hundred years old. It is extremely centralist, monolithic in approaching not only every problem with a single method but also citizens themselves with a single identity; a state model of the “mass production” era. It is impossible for this system not to generate any arbitrariness. If you were a prime minister, maybe you would begin to say “I need to be a president” in the fifteenth year of your term of office, and Mr. Erdoğan began to say this in his eight year. There is now such an order and law that enables one to select the location for the third bridge while hovering with a helicopter and to say “let’s skip 4G and move on to 4, 5 G Internet.” It is impossible not to fall in love with this power once you use it. It is precisely for this reason that there should not be a presidency. We have a complicated life requiring us to decentralize and democratize decision-making processes and to increase actors and focus points of these processes, but we are now discussing a system gradually centralizing and making everything uniform. This is not only a Mr. Erdoğan problem; we should be able to discuss this issue more calmly, regardless of his desire for presidency. The current parliamentary system is, in its essence, not much different from the presidency they wish for. So we cannot also propose this as a solution, but we are not able to discuss new solutions either, so we get nowhere.